The blogosphere flew into its usual uproar a few days ago when the inventor of the World Wide Web himself, the venerated Tim Berners-Lee, was recently recorded in a podcast calling Web 2.0 nothing more than a piece of jargon. There is little love and plenty of misunderstanding for this term in many quarters of the industry, despite the fact it has been painstakingly described by those that identified it to the world. For all the folks tired of hearing about Web 2.0 and very often not knowing what it means, there nevertheless remains the underlying reason for coining it: clearly apparent, widespread new trends in the way the Web is being used.

Of all the analysis I’ve read of the Berners-Lee podcast (and there’s a bunch, read Dana Gardner, John Furrier, even Dead 2.0), it’s Jeremy Geelan who has captured the real insight here with his post, “The Perfect Storm of Web 2.0 Disruption“, where he brilliantly explains what is probably the key to the real significance of the Web 2.0 phenomenon as a portentous crossroads between the old and the new:

Web 2.0 is an example of what the historian Daniel Boorstin would have called “the Fertile Verge” – “a place of encounter between something and something else.” Boorstin (and here I am wholly indebted to Virginia Postrel) pinpointed such “verges” as being nothing short of the secret to American creativity.

Postrel sums up what Boorstin was saying as follows:”A verge is not a sharp border but a frontier region: where the forest meets the prairie or the mountains meet the flatlands, where ecosystems or ideas mingle. Verges between land and sea, between civilization and wilderness, between black and white, between immigrants and natives…between state and national governments, between city and countryside – all mark the American experience.”— Jeremy GeelanWeb 2.0 Is Much More About A Change In People and Society Than Technology

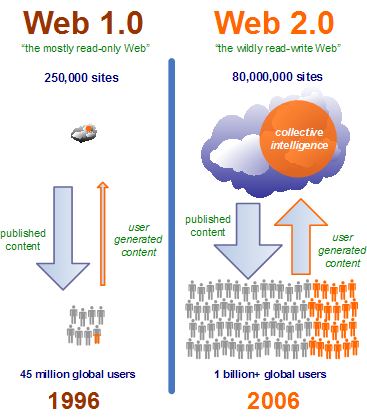

But is Web 2.0 really about the Web, or us? The rise of architectures of participation, which make it easy for users to contribute content, share it — and then let other users easily discover and enrich it, is central to Web 2.0 sites like MySpace, YouTube, Digg, and Flickr. But this is still just another aspect in the way that we, ourselves, have changed the way we use the Web. Not only have we gained 950 million new Internet users in the last ten years, but a great many of them use the Internet differently now too, with a hundred million of them or more directly shaping the Web by building their own places on the Web with blogs and “spaces”, or by contributing content of virtually infinite variety.

Let’s not forget that there were important issues that really held back the early Web and prevented the widespread flourishing of the collaboration and connecting of people that Tim Berners-Lee originally intended. This included privacy concerns, almost entirely one-way Web sites, lack of skills using the Internet, and even slow connections. But these have now continued to drop away rapidly in recent years, with many younger people in particular not hindered by these issues at all (rightly or wrongly.)

And for sure, let’s not forget that the Web has changed over the years. There have been countless technological refinements and even improvements to the physics of the Internet itself. These range from the adoption of broadband, improved browsers, and Ajax, to the rise of Flash application platforms and the mass development of widgetization such as Flickr and YouTube badges. But the trend to watch is the change in the behavior of people on the Internet. Because much of this Web 2.0 phenomenon comes from mass innovation flowing in from the edge of our networks; that’s millions of people blogging, hundreds of thousands more producing video and audio, hundreds of Web 2.0 startups creating hugely addictive social experiences, sites that aggregate all the contributed content that one billion Internet users can create and more.

Yes, the original vision of Berners-Lee is now apparently happening, so he’s right in a sense there while glossing over the reality of the early Web. But though his vision was largely possible since the advent of the first forms-capable browser, at first we only got what we could call “Web 1.0”; simple Web sites that were largely read-only or at least would only take your credit card. The essential draw of mountains of valuable user generated content just wasn’t there. And the millions of people with the skills and attitudes weren’t there either. Even the techniques for making good emergent, self-organizing communities and two-way software were in their very infancy or were misunderstood. An example: How long did it take the lowly editable Web page (aka wikis) to be popular and widespread? Nearly a decade. The fact is, most of us know that innovation is all too likely to race ahead of where society is. I run into folks from Web 1.0 startups fairly often that bitterly complain about how they were building Web 2.0 software in 2000, but nobody came.

What Exactly Is Special About The Web 2.0 Era?

I write frequently that we as an industry rediscover over and over again the same classic design issues right at the juncture of people and software, just repackaged enough so we don’t recognize them until it’s too late. This time around the sheer numbers and scale of the Internet have distorted our traditional, more parochial views of what we thought networked software was and online communities were. One outcome is the illusion that we had large degree of control over what happens when large groups of networked people can join together collaborate and innovate. We don’t. It’s like a large door has been opened behind us and everyone is now just getting a sense of that it’s there and where it leads.

But what exact is new here? I mentioned a few things, but a more complete list is better:

- There are over a billion Internet users now. Network effects can quickly climb in even small corners of the Internet, since small can now mean just a hundred thousand users.

- Many of these users have become profoundly Web-fluent. Robert Scoble observed recently that many users are still casual and non-expert, but almost all can search, they can post, they can edit a Wiki, and a lot of of them are now comfortable cutting and pasting Javascript snippets, and frequently much more. They are in control of the vehicle now.

- Powerful practices in Web site design are becoming widely known. The best and often most successful sites are finding out that carefully designing what Tim O’Reilly calls harnessing collective intelligence deep into the design of their sites can provide truly amazing results. And this aspect of how we use the Web is actually far behind the first two trends. It’s still surprising to me that many people cite Ajax as the exemplar of Web 2.0 and not building networked applications that leverage user contributions and trigger network effects. There’s quite a bit of headroom here in fact, and I expect to continue to see compelling advances in Web 2.0 software design.

- Thus, power and control is shifting to the new creators. As the users of the Web produce the vast majority of content (and soon, even software), they are therefore in control of it. This shift of control has enormous long-term consequences since the Internet tends to route right around whatever central controls try to be applied. The implications for traditional organizations are fascinating and will only increase as the MySpace generation heads into the workplace in large numbers.

There are more secondary trends related to Web 2.0 but the first three are the key, without all three, I would assert we would not be seeing some of the truly amazing things out on the Web that we see today. Is all of this “frothy”, as Robert Scoble recently claimed. Not in the slightest. Are people excited about it? Yes, and they should be. And while I don’t find the term itself to be particularly important — it’s the ideas behind it that are so interesting — the fact that so many people feel so strongy about the term Web 2.0 tells us that it’s something we should understand better.

BTW, in that last link Scoble was talking about The New New Internet, a Washington DC-based Web 2.0 conference I’m involved in. I can assure you it’ll be as far from content free as you can get and I do hope to see you there.