Well, it seems to be finally happening. The Web 2.0 sites are starting to bubble up — no pun intended — to the very top of the traffic charts, with MySpace and then YouTube eclipsing each other in weeks. The Guardian reported yesterday that YouTube is now commanding 3.9% of all Internet traffic, making it the #1 site on the Internet. That’s more than impressive given that they only started out in February, 2005. I’ve been covering MySpace and YouTube in my last two pieces (one, two) because they in particular seem to represent leading edge best practices in the social architectures of large-scale public Web sites. Ostensibly very “Web 2.0”, both MySpace and YouTube aggressively “harness the collective intelligence” of their user’s combined contributions as their primary offering to the world. In this sense, they have put their architectures of participation at the core of their product design. And wouldn’t you know it, it’s made them both leaders on the world stage.

But are they actually a flash in the pan? Do sites based primarily on participation really last? Won’t the next big site come along, and like YouTube seems to be doing to MySpace, just eclipse them? Yes, that’s likely to happen. In fact, it’s possible we’ll see an increasingly rolling wave of Web 2.0 sites overtaking each other, one after the other. The reason for this seems to be that the techniques for explicitly leveraging network effects and viral feedback loops is just making its big debut to the global software community. The techniques are still being refined and then one-upped.

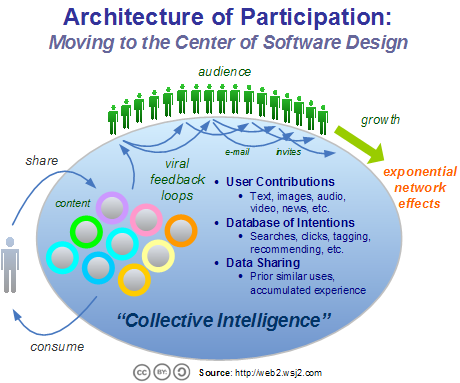

And yes, of course, none of this is actually new, it’s really all about the sea changes in the way people are using and designing for the Web, much more than the Web itself. So it’s less a technological change (though there are a few of those too) than a change in mindset and habit. Yet it’s having a very real effect on the sites that people visit and how they produce and consume information on the Web. At the core of all this is collective intelligence, the user contributed information on a site that is its powerful draw; if it’s the information they want that is. This can be user contributions in the form of text, images, audio, video, etc. Or it can be what John Battelle has long referred to as the Database of Intentions, which is often the 2nd order information about what other people thought about a given user’s contributions including search results, popularity statistics, clicking, tagging, etc. This can make contributions, especially popular ones, easier to find and locate, forming a sort situational awareness console for the Web (such as del.icio.us/popular) that creates traffic pile-ons spurring further growth. Finally, there is data sharing, the simple act of making prior decisions and their outcomes available to others, which is seeming the final sort of user contribution.

But a network effect is only an actual effect if it results in a successful propagation of attention and subsequent value. By this I mean that the content must draw in others in some way (who then contribute as well). And network effects are often be most effective when they’re carried in a social “push” process, such as when a friend e-mails a friend about their favorite new YouTube video. In fact, the end of each YouTube video makes it easy to do this. Offering this option was clearly one important decision in YouTube’s architecture of participation, as was making the video sharing badge process so easy to use by making the Javascript snippet to share it on your own site or blog available right next to each video, without having to ask for it.

Of course, you have to have valuable content or people won’t come back and they won’t push it to their friends. And though my good friend Jim Benson says that in this regard people should focus on quality communities vs. meteoric growth rates, the truth is that they probably go hand in hand. That doesn’t mean that YouTube hasn’t skirted copyright law to ensure it has the very best content to ensure growth. And that will be a question that will probably haunt them, and others that go down the route of that particular grey line, for a long time to come.

But generally, what this means for software, both inside and outside of organizations, is that the power of harnessing the innovation and output of your users will eclipse almost anything that centrally organized production could hope to match. Admittedly that’s with overall production quality a possible outlier in this model. But the point is that whether it’s consumers or employees, putting tools in their hands and driving creation fueled by self-interest (simple attention getting, but perhaps increasingly putting advertising in their contributed content?) can clearly result in a massive wave of relevant creative output. This is what is called innovation at the edge of the network, and it’s an amazing phenomenon that all of us are learning to tap by crafting the designs of our sites with an effective architecture of participation. And I’ll go on record, given the results so far, building competitive architectures of participation is almost certainly going to be one of the biggest topics in software design for the rest of the decade.

It’s almost like an arms race, but soon everyone will have the tools and techniques. What will happen after that? Equilibrium?